Major events

The Origin of Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day

By Éric Major, Pointe-à-Callière Historian

Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day – or the Fête nationale du Québec – is celebrated every year on June 24 as the days of the year stretch to their longest. June 24 coincides with the summer solstice, a day of pagan ritual dating back to the dawn of history that was first celebrated in homage to the light and power of the sun and to mark the start of farming season.

Taken over by the Christian Church as a religious holiday to celebrate the birth of Saint John the Baptist, this tradition grew deep roots in metropolitan France before finding its way to New France, where colonial archives refer to spectacular nighttime bonfires around which local libations flowed. Reports of one such dazzling fire held the evening of June 23, 1636, tell of how Governor Montmagny consecrated the pyre just before it was set aflame in a triumphant and festive moment set against a resounding salvo of musket fire.

As a liturgical event, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day took on new meaning during the English regime for French Canadians, who decided to adopt this day as a patriotic holiday to solidify their French union. At the initiative of journalist Ludger Duvernay, a banquet was held on Saint-Antoine Street in Montréal on June 24, 1834, about a future patriotic society dedicated to promoting French interests in the heart of the North American continent, a meeting that quickly took a highly political turn. The sixty attendees included lawyer John McDonnell, Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine, Édouard-Étienne Rodier, student George-Étienne Cartier, and Montréal Mayor Jacques Viger.

Historian Robert Rumilly reported that, for the occasion, Mayor Viger merrily sang the following three verses by an anonymous author, who exalted “our French forebearers”:

“They struck down tyranny, / We will strike it down as well. / As the hand of fate points to the enemy / St. John, lead us to victory.”

Galvanized by their noble aim, these men repurposed the annual celebration of Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day to make it a rallying symbol for civic pride and a focal point for the French national spirit. Two days later, the newspaper La Minerve gave a detailed account of their deliberations, as did the Quebec City newspaper Le Canadien, which enthusiastically reported, “We were very moved to read about the patriotic meeting held in Montréal regarding Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day, which has been adopted as a patron saint day.”

In Montréal, processions began on this date and, in 1843, they turned into a traditional parade with unwavering support from former Patriotes who wanted to bring French Canadians together and ignite their political and national passions, just as the English did with St. George, the Scots did with St. Andrew, and the Irish did under the banner of St. Patrick.

On the initiative of Ludger Duvernay, the Association Saint-Jean-Baptiste de Montréal officially came into being on June 9, 1843, at the St. Anne’s Market during a massive assembly of nearly all the city's French-Canadian dignitaries. As a charitable society whose mission was “to help and bring aid to people of French descent and contribute to their moral and social progress,” the Association articulated its principles and philosophy that same year, while its official charter was adopted a few years later during the turbulence of 1849.

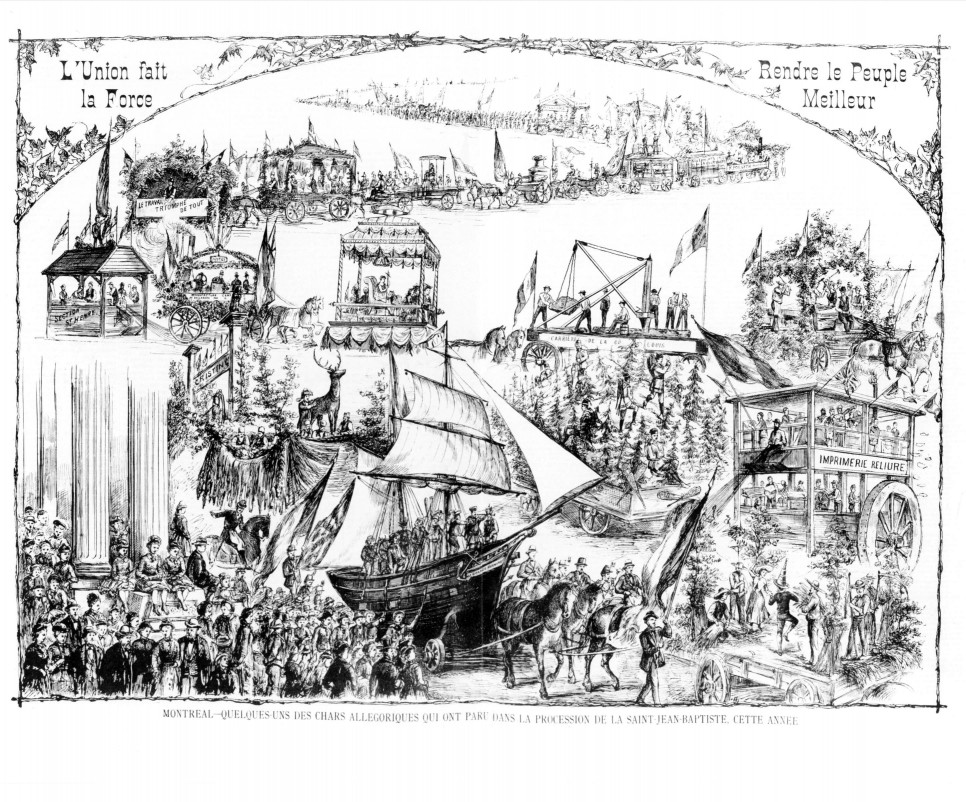

Traditionally begun with a Solemn Mass, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day became filled with copious banquets and lively, fiery speeches punctuated by hymns (O Canada, My Country, My Love), poems (The Carillon Flag), and even homegrown songs (A Wandering Canadian; Long Live the Canadian Woman). Eventually, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day led to bigger parades that would wind along a route of fir trees in a sea of banners, flags, triumphal arches, and symbols such as the beaver or maple leaf, while garlands and Chinese lanterns hung from the tree branches.

After the European model, floats were added in 1870 that gradually took on a more typical local colour. In 1855, a great variety of local figures became part of the processions to represent archetypal characters linked to New France's epic history. In 1868, however, the key figure of the highly embodied St. John the Baptist became almost too popular. As historian Jean Provencher explains, “The parades would include up to three St. Johns, which forced the Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste to adopt a by-law in 1902 forbidding the presence of more than one St. John the Baptist in the same parade.” For the tercentenary of the founding of Quebec City in 1908, Pope Pius X officially proclaimed St. John the Baptist as the patron saint of the French-Canadian faithful, an announcement that was greeted with jubilation.

Starting in the late 19th century, marching bands in Montréal and Québec City would provide a soundscape to the festivities that could be heard for miles. National themes, such as tributes to popular songs (1928), the French Canadian mother (1943), or the St. Lawrence River (“the road that walks”) (1959) were all motifs in a commemorative program that broadened the scale of this event meant to fan the flames of French Canadian patriotism.

The national pride honed by this June 24 tradition prompted La Belle Province to adopt new patriotic symbols, such as the fleurdelisé flag, which became the official standard of Quebec in 1948, or the white lily, which was adopted in 1964 as its floral emblem, followed soon by the blue flag iris, a more logical choice given that, unlike the lily, this flower actually belongs to Quebec's indigenous flora.

Over the decades, Saint-Jean-Baptiste Day celebrations have been influenced by the mood of the moment. During the 1960s and 1970s, they took on a tone of political protest, as people fervently advocated for their own country and the ideal of independence. The day would go on to become a more inclusive and participatory celebration deliberately open to Quebeckers of different origins to instill pride in all of the cultural communities that have helped shape this land into an increasingly mixed society.